- Home

- Kyra Wilder

Little Bandaged Days Page 3

Little Bandaged Days Read online

Page 3

When will she come and get them? E asked, watching me.

In the middle of the night, I told her. Princess Aurelie will come and get them when we’re all asleep.

There was an Aurelie though, a real Aurelie out there with arms and legs who sometimes got flowers given to her that were beautiful. Flowers that were just like these flowers, from someone who liked to imagine her at her doorstep, bending at the waist, picking them up.

I unpacked the bag from the market and discovered it was full of tram tickets. There must have been at least twelve of them, all time stamped with the date, today, and the time, right now. They were all good for an hour of travel on any bus, tram or water taxi in the city of Geneva. Handfuls of opportunities, there in fresh ink. Coffee on the Île Rousseau, macaroons at Ladurée, shopping or a dip in the wading pools at the Jardin Botanique. Anything.

It was just that I couldn’t remember stopping at the ticket machine. I could recall nothing of filling my bag with long strings of useless tickets. E and B ate the tiny tubs of yogurt. They were so fresh that they tasted like meadow grass. We ate them all up, one two three and so on, gobbling.

After breakfast I washed E’s hair and dried it with her favourite towel. I cut B’s nails and packed our bag for the park. The beautiful red tools. A purple watering can for the plants. Crackers, cucumber slices, a hunk of cheese. Simply getting ourselves to the little park behind our apartment was momentous.

E wasn’t helping and B was crying again. I thought maybe I would shout, Put your shoes on! Or else, Where is your other shoe! Or, Where is your hat! Then, suddenly and inexplicably and just like that, I was crying. I was holding B and my diaper bag and my beautifully packed snacks and toys in the hallway and crying in front of the door, and I found that my face was wet and also my hands from wiping my eyes and also my neck and the front of my shirt and B was looking at me and E was, and there we all were and there was no way to explain.

We threw a party when we left, M and me, for all our friends, to celebrate. His new job, our new lives, all of it. A real dinner party in our house, after he signed the contract and before it was empty, the house I mean. When we were still surrounded by everything that we loved and everything too that we were leaving. We threw a party and so many people came that finally M shouted, Leave the door open, just leave it, and I cooked salmon that was pink inside like kisses and we opened so many bottles of wine.

As a child, I had been obsessed with stories of covered wagons. The Wild West. Wagon trains riding off into the sunset. Children walking all the way to California. They moved so slowly, the wagon trains, that each night they were within sight of the place that they had camped the night before. I hadn’t been able to imagine it then, but now, of course, I understood how one could see easily places that can never be returned to. It could all be right before your eyes.

That evening I recycled the tram tickets, wrapping them in the paper the flowers had come in. Yellow lemony tissue. I threw it all into the bins.

3

There was a problem with my new Swiss credit card. It was cracked a little, just across the security chip. It was almost invisible, the crack, but in the end it didn’t matter that it was so small because I couldn’t use the card to buy things or to make withdrawals at the ATM. I kept having to ask M for money. He’d leave it for me on the counter and I’d use it to buy food or little presents for E when we were out. But I wanted to take things into my own hands as it were, and one morning I wrapped B in his swaddling blanket and set him all businesslike in his stroller and took E’s hand and we rode the tram into Geneva to go to the bank.

I showed my broken card at reception and an assistant led me into a private waiting room that was very white and had a large paper chandelier swanning down into the middle of it. E wanted to touch it and I did too but I told her no. B began to fuss in his stroller and I got him out to nurse him. I had my shirt hitched up and me everywhere out in the room when the assistant came back with the obligatory thimble of espresso and he was so startled that he dropped the cup. Of course this brought the cleaning crew but by then B was finished nursing and I set him smacking his lips and sleepy back into his stroller for a nap. I tucked my shirt back into my skirt and the assistant brought a second cup of coffee and we both avoided looking at each other while I took it and thanked him.

In the end though, there was nothing they could do for me at the bank. They said it like that, in beautiful English, over and over again. The account manager, the director and the managing director of the department. There is nothing we can do to help you. I kept asking to talk to someone else, but in the end there wasn’t anyone else. I spilled my wallet out and picked up all the pieces: my cards, my ID. This is me, I said. But the problem was, I wasn’t on the account. I was tired, B hadn’t been sleeping and I couldn’t, just really couldn’t think through what they were saying to me, the manager, the director and the managing director. For an instant I almost really went toppling over, my vision suddenly blurring, filling with the shapes of their faces, all smiling politely and nodding at me.

It was my residence permit, they told me. It wasn’t entirely complete, there was some stamp or other that needed stamping. Or, I had a different sort of permit that didn’t allow me to open bank accounts. I really couldn’t understand. Anyway I couldn’t be named on the account, they said, smiling at me, nodding at me, and instead M had opened the account in his name and given me a card for it. He must have forgotten to tell me, or been embarrassed to. I was embarrassed, there at the bank, with all my useless cards spread out on the table, and my sagging diaper bag and bottles and snacks jumbled and awful and taking up all their clean white space. But you can use the card of course, said the account manager, smiling, flicking her long hair back over her shoulder, even though it’s not in your name. But I can’t, I said, use the card. They offered me a second cup of coffee.

We left the bank and walked over to the lake and up to the pier where the Jet d’Eau shoots up and out of the water and you can feel the spray on your face and we did, feel it. We spread out our arms and turned in circles with all the other people who were visiting the city. Just feeling all that water land so lightly on our faces.

M was home and M was gone again. He called the bank and ordered me a new credit card. It’s so dumb, he said, that I couldn’t put you on the account. I meant to tell you. We’ll fix it later, he said. When I’m not so busy at work. We’ll figure something out. Sorry about this, I said. No problem, he said, really. Let me know if there’s anything else. No, I said, it’s OK.

Maybe we were residents of different countries now, me and M. There was, at least, an ocean of paperwork between us, stamps, seals, phone numbers to call, people to reach that could not be reached. Different kinds of permits permitting different kinds of things. Our credit cards were almost identical to look at, but of course that meant very little, or really that meant nothing at all.

As a girl I learned SOS in Morse code. I could flash it with a flashlight or rap it with my knuckles on a wall or counter. I could even signal it with my eyelids, with the way I blinked. In case a stranger took me by the hand and tried to make me get in his car, I could blink for help surreptitiously. I suppose, the main thing about what I assumed, was that someone would be there to come when I needed it, would be there watching me, waiting for my signal even. The trick, I must have thought, was only to know the right way to ask.

When I was a girl, I was often involved one way or another in elaborate games. They were like boats, the games, that sailed me from here to there, between the minutes, safely from one hour to the next. One summer my favourite game was called Flash-Flood. In the game I was stranded, alone, on a beautiful island. Everywhere the ground was carpeted with dry grass and beautiful flowers. In the middle of the island was a tree with a treehouse that could be accessed by a narrow wooden ladder.

During the game I would be the girl and the girl would pick flowers until suddenly, the girl would see a flash flood. Which is to say she wou

ld see water coming at her from a distance, rushing at terrible, even impossible speeds. The girl would scream. The girl was at all times both tragic and beautiful. The girl would fling her flowers down and run for the ladder and always she would pull herself up at the very last possible moment. Always the bottom of the shoe of the last foot into the treehouse would get wet. The point was to get to safety, but the point was also I suppose, thinking about it now, that the girl always did. That somehow, the girl always knew when to fling down the flowers and run. The right way to ask, the right exact moment to run away. Safety was always possible but it hinged on codes, secret knowledge and precision. The girl could save herself but only if she did everything right.

The flowers in the vase were dead now. Where is the Princess? E asked, looking at the flowers. Why didn’t she come? We both thought that maybe she’d been eaten by trolls, we both agreed that this was horrible. To myself though, I thought, that someone must send the real Aurelie flowers every day, that she must have vases overflowing and a path of petals leading from the flower shop to her apartment. To myself I thought that these flowers, my flowers, were, to her, to Aurelie, a drop in the bucket, nothing that she would miss or come looking for.

Anyway, they were hanging down over the top of the rental-company vase, their heads drying, the stalks melting slowly into goo, disappearing into the brackish water. I could never remember to get rid of them and so we, E, B and I, watched the deterioration. We noted the smells that rose from the water, the rot creeping up the stems. It was science, I told E. E took her animals, two plastic giraffes, a mother and a baby, one orphaned kangaroo, a baby orangutan and a white pony with dark spots, one by one to the edge of the vase to sniff the water. To gaze into it. Some of the fallen petals were collected to make a nest for the kangaroo. We were learning now by watching very carefully. Look, I said to her. Look at this and this and this.

I wasn’t sleeping, I really wasn’t. Not much. Not enough. E got up early. B stayed up late. In between the nights stretched, the hours drifting farther and farther from each other, like planets pushing outwards, always more and more alone inside the expanding dark. M was back sometimes and sleeping but he felt always very far away. When he didn’t come home I called my mother from the guest room and I’d gaze at the screen and not be able to make any sense of what she was saying. Go to sleep, she’d say, you look awful.

The days melted into each other. I felt it overwhelming sometimes that I was expected, all the time, to be a person. I woke in pieces. I was a random collection of parts. One shoulder but not the other, one ear. The skin on my face was raw, peeled open. I was so tired that it was really like that. It won’t last I thought. This is a phase, this is only now and now isn’t always. This minute is only this minute and this minute is only one minute long. Sometimes I would hang myself in the doorway, like a bat, with my arms and shoulders held at odd, rigid angles, and I would say Boo! to E when she came around the corner. Look! I would say, I’m a bat! Come be my bat baby, come be my baby bat and she would laugh and I would hug her little reed-body and wish suddenly, sharply, for this minute we were in to last for ever.

My hands were raw from washing dishes, from grappling with the unmanageable weight of wet laundry, from soaping hair, and brushing teeth. One night, I came back to myself with a start. It must have been two or three in the morning, one of those hours between children, when the apartment seemed to have no one but myself inside it. I found myself standing by the door, my hand on the door handle, my bag on my shoulder. I threw the bag down and tram tickets, whole streams of them, waterfalled out in a rush of paper, the ink black and fresh and gleaming, the paper curling around my ankles like inviting foam. I ran to check on B.

He was asleep in his crib and I woke him, shaking his shoulder a bit, my wet fingers leaving prints on his soft little sleeping shirt. Once he was awake he wanted me. I picked him up and shushed him. I settled with him on the sofa and slipped my nipple into his mouth for him to suck. There, I said, there, there, there. I’m here, I said. Here I am.

Afterwards, satisfied, I put him back down and I crawled into my own bed and we were all good and quiet then. Tucked in and up and away, each of us under our own clean sheets we were right in our right places and ready for M to sweetly find us, to kiss our cheeks when he came home, whenever it was that he did.

4

The next day came and found us though, in the early morning hours. B was hungry and we passed driftingly around the dining table, sitting down for just a minute in each place, the only guests at the party, sitting alone together in all the various chairs.

I wanted to make the empty room into a guest room. A really really perfect guest room. Everything would be white, I could see it, really see it in my head the way it would be. Towels, bedspread, pillow cases, sheets and curtains. Light and white. Glowing and scrubbed clean. Inside, everything would drift lazily, like on the best summer days.

I wanted sheets for that room that were so bright and clean that it would make anyone who slept there feel encompassed, touched, free. Like she would wake every morning with the sun on her face. There was a part of me that really believed sheets could do that, could make someone feel that way.

A bed would barely fit inside the little room, but that was all right, it would be like a ship. The way they look when they’re being built, when they’re girded and trussed in the yard. The bed would be like that in the little room. Hulking and wooden, well-outfitted with its prow pointed towards summer. What I’m trying to say is how deeply I imagined it, the room.

The only thing was the soap. I couldn’t see it. There must be soap to sit on the edge of the little sink in a white cup and the soap should be wrapped in a paper that was not white, paper of the most perfect colour. Something that would explain everything, keep the ship afloat, the white of the curtains billowing. Calm seas, white sand, warm sun. I couldn’t see it yet though. I couldn’t see that little part.

I was sitting on the grey rental-company sofa holding B as he fought off sleep, his small hands curling, as if digging himself out of a pit. As night turned into morning, I could feel the heat rising in the room, the sun beginning to boil the metal shutters, but I didn’t get up to open a window. He eventually drifted off making a little sound like a balloon does when it’s losing air and I fell asleep holding him, and woke to E’s eyes, held right up close to mine. Wake up, she said, wake up. Her animals were arranged in a ring around my feet, there were so many little painted plastic eyes looking at me. They’re hungry, E said.

We fed the animals sesame seeds. I made coffee. The smell of the beans tangled with the sweet rot from the flowers. The tram tickets in my bag, all stamped with yesterday’s date and good for an hour of travel in the middle of the night, I swept into a drawer in the kitchen with the other tickets, with all the things I meant to think about later, when there was time.

The heat crept into the apartment. It crept into our mouths and made our tongues too thick to lick our gummy teeth. We floated in pools of our own sweat, drifting as if we were holidaymakers floating down the lazy river on those swarms of plastic tubes. Let’s turn off the lights, I said to E. Let’s keep the shutters closed. Let’s make it dark inside and maybe that will keep away the heat. E liked it I think, so we let the ceilings hang over us like low clouds.

At the store, I attempted to make sense of the different detergents. Bottles to make towels soft, to remove spots of various kinds, to make whites white. Maybe they were for that, I didn’t know really. I couldn’t read any of the words. In the meat aisle E poked the dead, broken-necked chickens, each displayed on his or her own, individual styrofoam tray. Their plucked skin was the most beautiful pearly pink. E wanted to buy them, to cook them or love them for ever I couldn’t tell. Anyway it didn’t matter because I couldn’t touch them, could almost not go near them even, it seemed too brutal, to be on a tray like that, to be pressed and wrapped into it, unable to move. It seemed like something that was happening, it seemed urgent somehow to me then

that under all their graceful wrappings it would have been impossible to breathe.

In the afternoon I hung the laundry all around the house, and E and I pretended we lived in a forest, where all the children had, one day, quite suddenly and with no warning flown away, leaving only all their clothes, hanging on the branches. Weee we whispered to each other from among the branches, swinging.

At the park, I began to watch another mother with her children. She also came most afternoons to sit by the pump. She had a baby, a boy, maybe six months old, that she wore snuggled in one of those complicated wraps. She seemed to spin into and out of it, the wrap, without trouble, as if love made such a thing easy. She had another child, also a boy, about E’s age, who walked beside her along the clipped green hedges that lined the park, his hand in her hand, the space between them so lovely, like a garden, like a kingdom between their hips.

She carried her things easily, her bags I mean. A blanket for the baby, the toy the older child particularly wanted, snacks, a yellow washcloth, water bottles. She spoke with her baby as if they were in constant conversation, meeting his eyes, making him laugh. Rolling a ball to him over and over as if she could never tire of it. Singing to him. Leaving him easily, to push her son on the swing, to find his truck, to fill a bucket with water as if this was no trouble. Well, I was fascinated by all of it, the way she moved, the way she was, the way she loved them. I drank it up, maybe, is the way to say what I did, what I was doing watching her at the park. Drinking.

She was beautiful, her face was like a collection of interesting things arranged perfectly along the high shelf of her cheekbones. Arranged, as if to say look at this, or this, or this. A long nose, thick eyebrows, one crooked tooth. There was some wildness about her that I couldn’t place. That made me look back at her wondering. I couldn’t tell if her quiet poise meant calm or terror. I couldn’t tell what kind of animal she was.

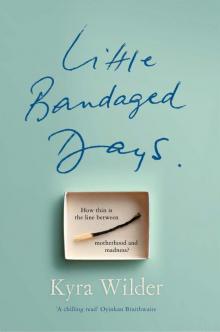

Little Bandaged Days

Little Bandaged Days